GMS Field Trip

If you have any questions about field trips send email toGMS Special Geology Tour

Tennessee

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Our guide for this special educational tour was a geologist who is extremely knowledgeable about the Tennessee impact structure. He explained the structure is about 8 miles in diameter and was created about 100 to 300 million years ago by an object that was probably ¼ mile in diameter. Compare that with the Barringer Crater in Arizona which is about 1 mile in diameter and was created about 50,000 years ago by an object that was probably about 55 yards across. The structure was discovered during railroad construction in the early 1860’s when engineers noticed formations that indicated a violent event had occurred there.

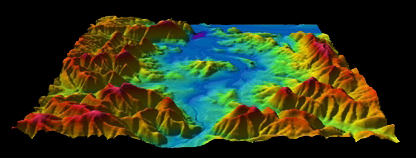

Stop 1 on the tour was on the eastern edge of the structure looking back towards the western edge. The geologist showed us a large topo map of the impact structure so we could see how the geology of the location had been thrown around and re-settled. Because it is a relatively circular area of deformed rocks, geologists originally believed it was volcanic, even though no evidence other than its resemblance to volcanic structures was present.

Further examination of the deformation and topological features plus the presence of shatter cones in the area led geologists to conclude that it is definitely not volcanic but almost certainly an impact site. There has been some debate about what kind of object created the structure. Because no meteorite fragments were found, some thought it may have been a comet, but most geologists who have studied the structure now believe the object was vaporized on impact and any remnants have eroded away.

Though we tend to think of it as an impact crater, it is actually the remnants of an impact crater. Based on the age of the exposed strata, which in some places are vertical or completely flipped over, the impact occurred 100 to 300 million years ago. It has been estimated that the structure was formed in one tenth of a second and the remainder of the structure within another second or 2, though it may have taken a few more seconds for ejected material to settle. What we see now is not really a crater, but what is left of the crater after about a thousand feet of older and newer sedimentary deposits have eroded away.

One of the formations that make the area particularly interesting is the shatter cones. The shatter cones were formed by massive shock waves from the tremendous force of the impact. The pattern is, as one would expect, conical, and theoretically, they point towards the source of the impact. On a GMS trip to the structure in March 2013 (click here for the trip report), we were able to collect these unusual, enigmatic bits of rock. Unfortunately, there had been so much rain in the area that we could not collect any on this trip, but the geologist generously brought plenty of samples for everyone.

Stop 2 on the tour was to see beds of Devonian and Upper Silurian ages that dip into the central uplift rather than away from it. The geologist showed us a photograph of a chevron fold caused by a fault that is a “circular fault that surrounds the structural central block and coincides with the periphery of the topographic outer angular ridges”.

Stop 3 was near a fishing area where we got to see a boulder of megabreccia that was most likely removed from the center of the structure to be used as rip-rap.

Stop 4 was on the south end of the structure where we could see a point where two faults come together.

Stop 5 was almost at ground zero. At first, you would think ground zero would be a depression, “but here, on the Moon, Mars, Mercury, and other bodies, some crustal and mantle conditions result in a rebound that lifts deep material up into a central peak in a basin. There has been considerable erosion; so, what is left is a small hill that we could clearly see, even from a distance” [Bob].

Stop 6 was to see more indications of the impact, but the area was so overgrown we could not see them. It was still a lot of fun though, because Charles jumped off a small bridge to look at the rocks and we wickedly enjoyed his chagrin as he struggled to get back out, which he ultimately did with great strength and agility (added that last part just for him).

Finally, we explored a few more secret spots where we collected some secret stuff plus some sand :o)

Thank you to our wonderful geologist friend for this fascinating and educational tour!

[Report reviewed and revised by Bob and Olga Jarrett]

Lori Carter, on behalf of

Charles Carter, GMS Field Trip Chair

e-mail:

Photo by Lori Carter

The geologist explaining the impact structure with a large topo map

that he used for reference on each stop of the tour

Photo by Lori Carter

Standing on the eastern edge of the structure, we could see the western edge

http://www.astrosurf.com/luxorion/impactlistecrateres2.htm

What we see now is not really a crater, but what is left of the crater

after about a thousand feet of older and newer sedimentary deposits have eroded away.

Photo by Lori Carter

Shatter cones were formed by massive shock waves from the tremendous force of the impact

Photo by Lori Carter

Beds of Devonian and Upper Silurian ages dip into the central uplift rather than away from it

Photo by Lori Carter

This boulder of megabreccia was most likely removed from the center of the structure

to be used as rip-rap near a fishing area nearby

Photo by Bob Jarrett

Close up view of the megabreccia above

http://craters.gsfc.nasa.gov/assests/images/craterstructure.gif

The impact structure is an example of a complex crater,

the main difference being the central uplift

Photo by Lori Carter

From the south end of the structure we could see a point where two faults come together.

Photo by Lori Carter

Because of central uplift and a great deal of erosion, ground zero is not a big hole.

It is the small hill you see in the distance

Click below for field trip policies

Copyright © Georgia Mineral Society, Inc.