GMS Field Trip February 2024

If you have any questions about field trips send email toGMS Field Trip

Pseudodiorite, Slag, and Sericite after Staurolite in Tennessee

Saturday, February 17, 2024

We knew we were going to face some cold weather that morning as tiny snowflakes drifted down to greet us. Charles distracted the group from the cold by talking about the history of the site and by showing us some examples of what we could find that day. After we arrived at the site, we signed waivers in an office adorned with black and white photographs, detailed maps, mining artifacts, and rock samples that allude to the site’s history and geology.

When copper ore was mined from this geologically rich basin in the mid-1800s, ore smelting released sulfur that reacted with atmospheric water to form sulfuric acid. For years it rained destruction upon the area, killing vegetation for miles around until all that was left was a lifeless landscape. By the early 1900s, processes were modified to capture the sulfur instead of releasing it into the air, but the damage had been done. Environmental remediation efforts began in the late 1930s and continue to this day. The massive brown and red scar of dead dirt was so stark and unforgiving that it was visible from space more than a century later. Ironically, the sulfur became a viable commodity and ultimately surpassed copper as the primary product, even after mining ceased in 1985. Current operations are dedicated to clean-up efforts while making use of native rocks and mountains of iron slag left from decades of smelting.

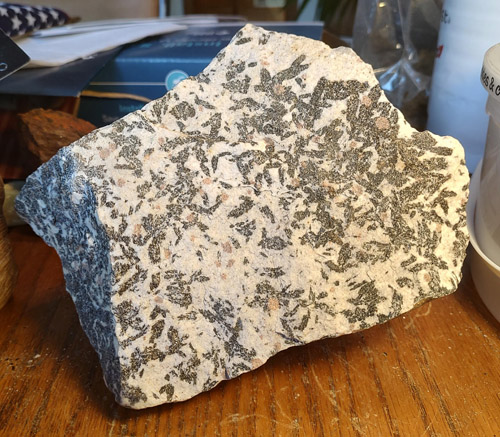

History was all around us as we drove past long-abandoned production facilities, red brick buildings with hints of deco design, and other artifacts of what was once an operation so large it had its own fire station and airport. The first stop of the day was at a small quarry. Members collected samples from boulders of dark greywacke sandstone that had large lenses of pseudodiorite in them. The pseudodiorite is composed of white quartz and plagioclase feldspar peppered with black hornblende crystals and ghosts of pink garnets. It is classified as “pseudo” because its composition differs slightly from the strict definition of diorite, that, like the pseudodiorite, is composed of plagioclase feldspar and hornblende but also includes biotite mica and does not contain quartz or garnets. In addition, diorite is igneous, but the origins of the pseudodiorite are thought to be sedimentary. Whatever you want to call it, the rock has a wonderful contrast of minerals resulting in an attractive rock that is as pretty as it is geologically interesting.

Next, not far from the quarry, members perused a pile of iron slag that was left behind as a by-product of the copper ore processing. Small pockets in the slag often contain microscopic crystals. Some have yet to be identified, while others have been identified as gypsum in various forms including long thin crystals, radiating sprays, and tight little puffs. The slag itself can have weird shapes and patterns that are fun to collect. A curious example of that is red slag with cracks filled in by silvery slag. It has a decidedly reptilian appearance, so we call it “slagon skin” and opine that it must have been shed by fire-breathing furnace dragons that melted the copper ore.

Our final destination was a wooded area where members dug and screened for sericite after staurolite. Single crystals, often called blades, can reach up to 6 inches in length and can be as wide as 3 inches. The staurolite is altering to sericite, a type of mica, but the original staurolite can still be found at the heart of many crystals. BB-sized almandine garnets are often seen embedded in the sericite. Besides finding specimens for ourselves, our special goal was to find a 90-degree twin “fairy cross” for the property owner. We haven’t found a fairy cross for him yet, but one of the members found a 60-degree twin “X” for him on the trek back to the cars!

The property owner always welcomes us warmly and goes out of his way to accommodate us. For this trip he put slag gravel on the quarry road so cars could get through muddy areas, mowed a pasture for us to park in, and dug up the staurolite area to make it easier for us to find specimens. Throughout the day, members expressed their gratitude for the opportunity to explore such a unique geological area. There are no words to describe how grateful we are for his incredible generosity, and we hope he knows how much it means to us. We must also thank the field trip attendees for diligently following safety rules and for being quick to lend a hand to fellow rockhounds. And, of course, thank you to Charles for organizing yet another fantastic field trip!

Lori Carter

On behalf of Charles Carter, Field Trip Chair

e-mail:

Location 1: Cold Wind and Pseudodiorite

Photo by Al Klatt

Wide view of the quarry

Photos by Al Klatt

Some schist and pseudodiorite followed by a close-up of the schist

Photo by Al Klatt

Pseudodiorite lenses in the greywacke

Photo by Al Klatt

Broken lens with both materials visible

Photo by Al Klatt

Just pseudodiorite

Photos by Lori Carter

Views around the quarry

Photos by Lori Carter

Large boulders with pseudodiorite plus a close-up of the lenses below

(Note: this is the same set of boulders in a prior image but from a slightly dofferent angle)

Photo by Lori Carter

Another pseudodiorite lens

Photo by Lori Carter

A specimen with the edge of a lens

Photo by Lori Carter

A nice hand specimen with both pseudodiorite and greywacke

Photo by Lori Carter

Pseudodiorite polished on one side highlights the beauty of this rock

Location 2: Here there be slagons!

No photo by Lori Carter

I forgot to take a picture of the slag pile,

but imagine hills of slag with more pieces of slag than one could possibly peruse in a lifetime.

Photo by Ken Scher

A big hole in a big piece of slag

Photo by Lori Carter

A big piece of slag from a big hole in a big piece of slag

Photos by Lori Carter

Slag we can appreciate simply for their shapes

Photo by Lori Carter

Slagon skin!!!

Photos by Lori Carter

This slagon had some battle scars

Photo by Lori Carter

Part of a slagon finger including the knuckle

Photo by Lori Carter

Not sure what these criss-crossing things in the slag might be...

Photos by Lori Carter

Microscopic gypsum crystals are "blooming" all over the slag

Photo by Ken Scher

Beautiful micromineral in some slag, probably gypsum

Photo by Ken Scher

Not sure what these stunning micros are

Photo by Ken Scher

Lacy micro crystals

Photos by Lori Carter

Some beautiful green micro crystals

Location 3: Sericite After Staurolite

Photos by Lori Carter

Members set their sights on some sericite after staurolite!

Photos by Lori Carter

One of the first specimens of the day. Note the diamond shape that confirms ID.

Photos by Lori Carter

Another nice specimen straight out of the ground

Photos by Lori Carter

Some crystals were in soft matrix

Photo by Lori Carter

This one was already broken, but now you can clearly see the diamond shape of this crystal

Photo by Lori Carter

Al Klatt found this matrix with voids left by crystals

Photos by Al Klatt

Al's matrix cleaned up a bit plus an assortment of crystals and core samples he found

Photo by Al Klatt

One of Al's favorite crystals

Photo by Al Klatt

This large crystal that Al found still has a lot of staurolite inside

Photos by Lori Carter

This naturally broken crystal shows how the sericite is replacing the staurolite

Photos by Lori Carter

You can see the staurolite inside plus the garnets embedded in the sericite on the outside

Photos by Lori Carter

In the ground and out of the ground

Photos by Lori Carter

The X twin!

Photos by Al Klatt, Ken Scher, Lori Carter

We were treated to this serene view of snow-kissed trees on rolling hills in the distance

Click below for field trip policies

Copyright © Georgia Mineral Society, Inc.