GMS Field Trip August 2023

If you have any questions about field trips send email toGMS Field Trip

Behind-the-scenes Fossil Site and Museum Tour

in Tennessee

Saturday, August 19, 2023

Facing the prospect of temperatures soaring into the 90’s, we were fortunate that the Knoxville Gem & Mineral Society (KGMS) invited GMS members to join them on multiple field trips where we could avoid the intense heat of the day. Our first stop was the Gray Fossil Site and Museum in Gray, TN. Mick Whitelaw, professor at East Tennessee State University and KGMS member, arranged a special tour for us with no entrance fee, but we all happily donated to the museum to help them continue the important work there. Mick and David Moscato, Science Communication Specialist at the Gray Fossil Site who was also involved with the site as a graduate student, led our group on a fascinating tour of the site and facilities.

David explained why this fossil site is different from other fossil sites. One of the most remarkable aspects of the site is that there is a large diversity of animals and plants that provide a detailed picture of the ecosystem that existed there during the Early Pliocene Epoch about 4.5-5 million years ago. The fossils are protected by the clay that surrounds them, so work can be done slowly and meticulously. The dig site is right next to the processing lab and collections storage, so volunteers and researchers don’t have to move specimens very far, can work on specimens year-round, and can be comfortable doing so. Contrast this with fossils sites in arid regions where weather conditions allow for collecting only during certain months and are so far away from cities and towns that dig personnel must camp for weeks at a time, then carefully pack fossils and transport them to labs. As of this writing, more than 30,000 specimens have been cataloged, including hundreds of new species, with new discoveries every year.

Standing in in front of toothy fossil replicas, David gave us a brief history of the site and the kinds of animals found there. Fossils were discovered during road construction in 2000. Pressure from the public and researchers convinced the state to reroute the road, and the site was preserved as part of East Tennessee State University. The museum opened in 2007. Animal fossils found so far include tapirs, rhinos, mastodons, red pandas, camels, turtles, birds, frogs, rodents, and recently, a bone crushing dog identified by a single humerus bone. Plants include oak, hickory, and pine trees like those that are still common in the area today, as well as flowering plants, fungus, and algae. In addition to plant fossils, fossilized pollen is used to identify plants. Some of the animals and plants have been found only at this site. We were surprised to learn that original material is found, i.e., fossils are not completely silicified or replaced by minerals. This prompted one member to ask if DNA has been extracted. Though it has been attempted, no DNA has been retrieved yet.

We viewed the excavation pits from an outside balcony where David and Mick talked about the geology of the site. Limestone formed from an ocean 480 million years ago. Sinkholes formed and became ponds. Sediment filled the ponds and preserved plants and animals that died and sank into the mud. Sediment built up in layers within the sinkholes, preserving an astounding amount of information about the ecosystem there. With a better understanding of how the fossils ended up there and how they were preserved, we walked down to see the actual dig sites. Multiple pits are right next to the museum. We saw the pit where a small rhino nicknamed “Little Guy” and larger rhino nicknamed “Big Boy” were found. In the pit next to the rhino pit, there is a bigger pit where a large mastodon was found as well as a rhino nicknamed “Papaw” that, based on the wear on its teeth and how its bones were fused, has been determined to be of more advanced age than Little Guy and Big Boy. Large bones are taken from the dig sites to the prep lab, while small fragments and the surrounding sediment are bagged for processing later. While we were there, we saw volunteers sifting through bags of sediment from prior digs. Fine clay is removed with water, and what remains is dried.

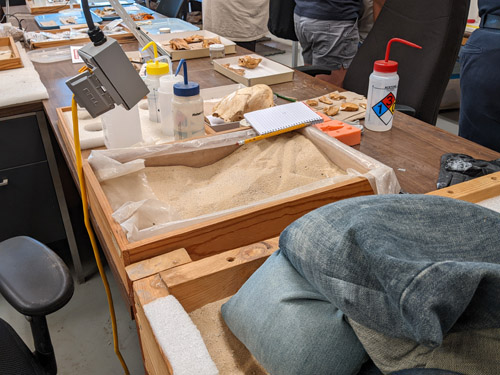

Back inside, David and Mick gave us a behind-the-scenes tour of the prep lab. Researchers and volunteers sort bone fragments, clean them, stabilize them, then piece them together. Where there are small gaps in bone puzzles, a special substance called Butvar is used to build web-like scaffolding to hold bone fragments in place, but it can be completely removed later if necessary. Where there are large areas missing, parts can be 3D printed based on completed areas. Rather than put the bones together into a skeleton, they are stored separately, even when there is a mostly complete skeleton. This protects the fragile bones from damage and makes it easier to store them. Models of the original skeletons are cast for museum displays. We saw part of Papaw’s jaw and we could see up close how worn his teeth are. We also saw a mastodon skull that is being pieced back together. Sand tables are used to hold large pieces in place as they are being reconstructed so they can be repositioned without placing too much pressure on the delicate bones.

After the lab, we toured the collections room where fossils are stored. A special environmentally controlled room has rows of large archival cabinets that contain multiple specimens. Only acid-free archival paper and pens with archival ink are used to ensure the safety and longevity of labels. Everything is carefully cataloged including where each piece was found so researchers know the exact layer and orientation of the fossils. Even hand-written notes are scanned and saved in the database.

We finished the tour on our own by walking around the museum to see the exhibits. In addition to the fossil exhibits, I particularly enjoyed the augmented reality sand topographic map table. Contour lines and colors are projected onto a sandbox filled with white sand. As you move the sand around, elevations are altered and the projected contour lines and colors change to match. Charles built a caldera and left it for children visiting the museum to fill with digital water.

After a break for lunch, we reconvened in Bristol, TN. Mick arranged a special group rate for us to tour Bristol Caverns and supplemented the standard tour with information about the geology we were seeing deep underground. He explained that the caverns were formed by limestone composed of bedded layers of sediment, and indeed, layers made distinct by algal mats were clearly visible. The limestone was scoured by underground rivers that gouged large voids. Cracks in the bedded layers allow water to seep into the voids bringing dissolved calcium carbonate drop by drop to form spectacular speleothems including stalactites, stalagmites, and graceful drapes of “bacon”. Silica left by sponges formed chert nodules that we could see embedded in the limestone. Mick explained how stalagmites that were broken, but remained in place with the lower parts a few inches below the upper parts, ended up that way not from earthquakes, but from the bottom of the cave settling and shifting down a bit. The caverns themselves were formed by successive catastrophic collapses.

On the way home, Daniel Miller, Knoxville Gem and Mineral Society field trip chair, led us to the last location for the day. We stopped at a small, unassuming place to collect graptolites – colonial marine organisms that lived during the Ordovician period about 480 to 430 million years ago. There are graptolite species still living today that help paleontologists understand the morphology of the fossil species. Graptolite fossils are often flattened echoes of the colonies rather than three dimensional structures, so we searched through shale for sawtooth shapes and found many good specimens very quickly. It was a great way to finish a great field trip.

This trip would not have been possible without Mick Whitelaw. He arranged the behind-the-scenes tour at the Gray Site and Museum as well as the tour at Bristol Caverns and provided information all day. David Moscato gave us an incredible tour of the Gray Fossil Site. He and Mick explained what we were seeing, gave us background stories, and answered all of our questions. Many, many thanks to Mick and David, as well as Daniel Miller for pulling all of this together and for taking us to collect graptolites!

Lori Carter

On behalf of Charles Carter, Field Trip Chair

e-mail:

Gray Fossil Site and Museum

Photo by Lori Carter

The brick wall in front of the museum artistically depicts animals that once lived there

Photo by Lori Carter

David Moscato introduced us to the site with a history of the fossils and the site itself

Photo by Lori Carter

David and the fossils were intrigued by something to the right...

Photo by Lori Carter

One of the juniors had the privilege of holding a copy of a turtle shell for everyone to see

Photo by Lori Carter

David and Mick continued telling us about the site from an outdoor balcony

Photo by Lori Carter

There are several pits close to the museum. The small hill is what is left of the hill that was here before.

Photo by Lori Carter

The mastodon pit where rhino Papaw was found

Photo by Lori Carter

Volunteers were washing and screening sediment when we were there

Photo by Lori Carter

Bags full of sediment waiting to be processed

Photo by Lori Carter

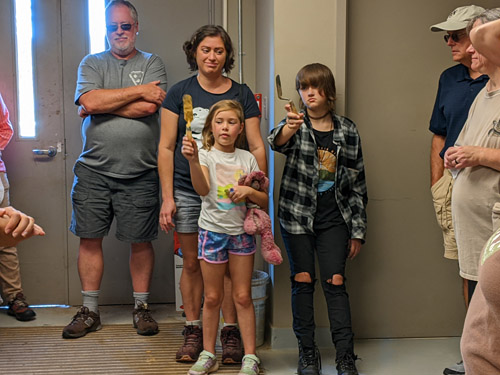

Juniors held up trowels that have had the edges rounded to protect fragile fossils

Fossil Prep Lab

Photos by Lori Carter

We got a special tour of the prep lab

Photos by Lori Carter

Papaw fossils including part of his jawbone and a close-up of one of his teeth

Photo by Lori Carter

Mastodon skull being reconstructed

Photo by Lori Carter

3D printed pieces fill in for missing parts

Photo by Lori Carter

A substance called Butvar can be used to build scaffolding for missing areas

Photos by Lori Carter

Sand tables allow positioning fossils for reconstruction without placing pressure on delicate bones

Photo by Lori Carter

Every day items are used for prepping fossils, though they may be modified.

Note how the bristles on one of the toothbrushes have been shortened to an angle.

Photos by Lori Carter

Microfossils include plant material like these grape seeds (top)

and small animal fossils like these frog limb bone fragments (bottom)

Collections Room

Photos by Lori Carter

Fossils are stored in large cabinets

Photos by Lori Carter

Archival paper and pens with archival ink are used

Photo by Lori Carter

Replica of a tapir skull on display in the collections room

More Sand in the Museum

Photos by Lori Carter

Visitors enjoy this augmented reality topographic map table.

Contour lines and elevation colors are projected from above.

The lines and colors change in real time as the sand on the table is moved around.

Charles made a caldera that juniors couldn't wait to fill with digital water.

Bristol Caverns

Photo by Lori Carter

Beautiful cave formations greet visitors as they enter the caverns

Photo by Lori Carter

Beyond the beauty, Mick pointed out a cave formation that fell on its side

so long ago that more cave formations grew over it.

Photo by Lori Carter

This stalactite was beginning to connect to the stalagmite below when the ground shifted down.

The stalactite broke, but remained in place as more calcium carbonate deposited over it.

Photos by Lori Carter

(Top) Limestone with visible sediment layers. Over time, it tilted and is now the "ceiling" in the cave.

(Bottom) A piece of the same kind of layered sediment limestone on display at the Gray Museum.

Microbial mats separate the layers and make them more distinguishable.

Photo by Lori Carter

These odd little stalgamites have "splash cups" on top that were probably caused by rapidly dripping water

Photos by Lori Carter

An underground river carves through the limestone and contributes to the formation of caverns

Graptolites!

Photo by Lori Carter

First graptolites of the day!

Photo by Lori Carter

Some classic specimens

Photos by Lori Carter

Faint, but close-up shows some good graptolites

Photos by Lori Carter

Superb graptolite specimen

Photos by Lori Carter

More classic specimens

Photos by Lori Carter

Graptolites everywhere!

Photos by Lori Carter

An unusual specimen

Photos by Lori Carter

Last one of the day was a big one!

Click below for field trip policies

Copyright © Georgia Mineral Society, Inc.