GMS Field Trip February 2023

If you have any questions about field trips send email toGMS Field Trip

Various Rocks, Tour, and Slag in Tennessee

Sunday, February 19, 2023

The mining history of Copperhill, TN is a mind-boggling tale of unimaginable environmental disaster. Copper mining started in the mid-1850s and quickly became the dominant industry in the area. The ore did not contain large veins of copper, so it had to be crushed and heavily processed to remove the metal. During a roasting phase, sulfur was released into the air. The sulfur combined with water to become sulfur dioxide that rained down on the mining community. Within a few years, the area was devoid of trees, partly from the acid rain, but also because so many trees were cut down to fuel the smelting processes. By the late 1800s, the environmental impact was undeniable and spawned several lawsuits. In 1904, smokestacks were installed to help contain the sulfur, but ironically, they actually spread the toxic materials even farther. In 1907, faced with the prospect of being shut down completely, mining engineers installed condensers to capture the fumes and produce sulfuric acid as a viable product rather than as disastrous waste. Unfortunately, it was too late. The damage was done. As early as 1939, efforts to reverse the damage began with reforestation projects. By 1987, mining and processing had ended. Abandoned shafts, mining equipment, and buildings lay fallow. The acidic environment and inevitable decay wrought by time caused more environmental damage from erosion as silt made its way into local waterways, choking reservoirs and threatening aquatic life [1].

Today, trees and native vegetation are flourishing, and life has returned to waterways. A local company has continued the work of cleaning up the area with great success and continues to do so. Charles and I had the pleasure of meeting the owners, Buddy and Sarah, and have had several tours around the property. Besides the dubious history of the area, it is also geologically fascinating. Even the slag left behind is filled with mineralogical interest.

Buddy and Sarah are now members of GMS, so they invited the club to have a field trip! There are so many places of interest on the property that Charles had to narrow them down to what would be realistic for a day of collecting. With help from Buddy and Sarah, he chose three locations for the trip: a rock quarry, an ore bin, and a massive slag pile.

Members arrived early in the morning to complete liability waivers. Buddy gave a brief introduction and explained safety rules. Donning high visibility safety vests, the group explored the quarry first. When I talked to Kim Cochran before the trip, he explained that the rock there that we loosely call diorite is actually pseudodiorite. Diorite is an igneous rock that typically contains plagioclase feldspar, biotite mica, and hornblende, but a paper published in 1926 says the rocks we collect may have sedimentary origins. The paper argues that, like textbook diorite, the pseudodiorite contains feldspar, and hornblende, but it also contains garnets, and can contain as much as 25% calcite. Plus, the texture is similar to the surrounding sedimentary rock, a type of sandstone called graywacke. Another paper published in 1913 points to other rocks in the area that contain calcareous concretions as an indication that these types of concretions underwent intense metamorphism with the graywacke to form the pseudodiorite [2]. Since then, very little information has been published about the material, so without further study, current geologists are not convinced that the sedimentary origin conclusion is accurate. Whatever its origins may be, it is a beautiful rock and the uncertainty of its origins makes it even more fun.

For our second stop, Buddy led the group on a tour to see an old ore bin. He explained there was a mining shaft nearby where the ore was brought up and loaded into the large concrete structure. Train cars would be positioned below the bin and filled with copper ore. We saw remnants of the old tracks on the way to the bin. The area around the bin is still highly acidic, so we did not collect any samples, but we saw decomposing pyrite and some small, pink garnets weathering out of decomposing rocks. On the sides and below the ore bin we saw formations similar to those seen in caves. These urban speleothems are called calthemites and are a spectacular side effect of years of water leaching sulfur and other substances through the concrete and depositing them layer by layer. Just past the ore bin we saw more formations in a creek. The calthemites in the creek are unusual terraces reminiscent of travertine terraces that form near hot springs and geysers as calcium carbonate precipitates from water. These terraces are forming as iron precipitates from water that still has a pH of 2! As oddly beautiful as they are, the terraces and the acidic water around them are still a stark reminder of the astonishing scale of the damage caused more than 170 years ago. Buddy explained that they are using various methods to clean the water and reiterated their dedication to that work.

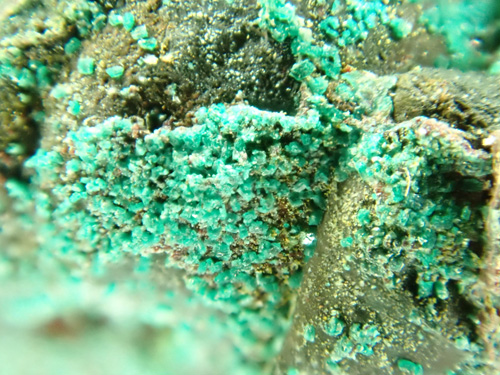

After touring the ore bin, we went to play on an enormous slag pile. The slag there is a waste product of smelting the copper ore. It consists of mostly iron, silicon, and calcium. We know it also has some copper in it because we saw many pieces with green and blue colors. The slag has interesting flow patterns so it was fun to collect just for that, but we also found crystals in the slag. Some spectacular clusters of gypsum crystals identified by Micromount Section chair Julian Gray (via text message all the way from Oregon!), were large enough to see with the naked eye. There were also micro clusters of gypsum crystals “blooming” everywhere. Neon green and pale blue coatings were initially thought to be paint – yes, they are that neon – but upon further inspection we realized they are truly a natural coating. They fluoresce under shortwave light too! Some tiny puffballs of white crystals are as yet unidentified, and some extremely small, deep green cubic micros are also still a mystery.

Before the day was over, a few diehard members had a chance to help find some pseudomorphs of sericite after staurolite. We found several large crystals, some 5 inches or longer and more than an inch wide. Some specimens are not completely altered, so the centers are still staurolite. The pseudomorphs are in an area that will be cleared and built over soon. We hope to have a field trip or multiple trips to collect them before they are no longer accessible, so stay tuned!

It is hard to find the words to express how grateful we are to Buddy and Sarah for inviting us to collect at this unique geological area. Each place we visited had so much to see and discover and collect that we forgot to break for lunch! From the moment they welcomed us that morning until the sun was setting that evening, they were attentive hosts making sure we were safe and having fun. Thank you, Buddy and Sarah and our new doggy friend Daisy May! Thank you to Tom Faller and Ken Scher for helping with initial prospecting, Perry Curl for helping with prospecting during the trip, as well as Travis Paris and Kim Cochran for their help explaining the geology. Thank you to all of the members who added to this place’s history by being a part of the first rock club field trip there since mining ceased. And, of course, thank you to Charles for arranging this incredible trip!

References:

[1] Webpage, Cochran, K., 2019, The Copper Basin "Minerals and Mining of The Copper Basin", URL https://www.gamineral.org/writings/copperbasin-cochran.html/ (accessed 2/20/2023).

[2] W. H. Emmons, F.B. Laney, with the active collaboration of Arthur Keith (1926), Geology and Ore Deposits of the Ducktown Mining District, Tennessee, Professional Paper 139, Department of the Interior

Lori Carter

On behalf of Charles Carter, Field Trip Chair

e-mail:

Rock Quarry

Photos by Lori Carter

Graywacke and pseudodiorite as well as other rocks were plentiful and easy to collect.

Note the large pseudodiorite areas (light color) in the boulders.

Photo by Lori Carter

This specimen shows the dark graywacke and the light pseudodiorite

Photo by Lori Carter

Close-up of the rock above. The dark bits are hornblende and the pink bits are garnets.

Notice how the close-up shows the granularity of the pseudodiorite, an indication that it is metamorphic, not igneous.

Photo by Lori Carter

Charles did a quick face polish on a piece of the pseudodiorite

Photos by Ken Scher

Ken found some pretty pieces of the pseudodiorite

Ore Bin

Photo by Lori Carter

Train cars would be filled with copper ore from the ore bin

Photos by Lori Carter

Calthemites, i.e., urban speleothems, on and under the ore bin

Photos by Lori Carter

Terraces formed by acidic water

Photo by Ken Scher

Another view of the terraces

Photo by Lori Carter

Decomposing pyrite. This probably started as a larger mass of pyrite.

Photos by Lori Carter

Decomposing rock dotted with pink garnets

Photos by Lori Carter

Actinolite specimen

Photo by Ken Scher

Photo by Lori Carter

Unusual mushroom thriving in the acidic soil.

Ken identified it as being in the Diplocystaceae family.

Slag

Photos by Lori Carter

Plenty of slag to peruse

Photo by Ken Scher

Photos by Lori Carter

The slag has interesting patterns and colors

Photo by Lori Carter

It can look like abstract art

Photo by Lori Carter

It can look like coprolite too

Photo by Lori Carter

It can even have crystals in it. These were found not long after we hit the slag piles.

Photos by Lori Carter

Here is the slag with the cluster above to show scale, plus another close-up from a different angle.

Photos by Lori Carter

More gypsum clusters in slag

Photos by Lori Carter

Bob Dolezal's slag with gypsum crystals

Photos by Kyle Ward

More gypsum photos and some unidentified micros from Buddy

Photos by Lori Carter

These super tiny crystals (about .1mm) were difficult to photograph.

Eventually we will have some good images of these and hopefully ID for them too.

Photos by Lori Carter

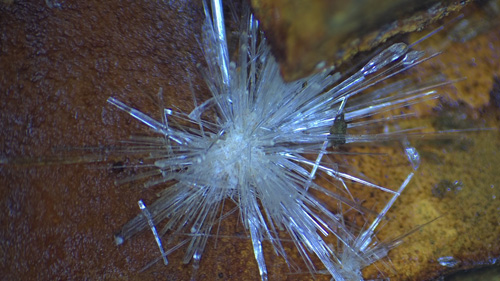

In addtion to cubic crystals, there is a pretty spray of crystals on this specimen

Photos by Lori Carter

Some tiny puff ball crystals

Photos by Lori Carter

These crystals were found as a crust on top of big chunks of slag

Photos by Lori Carter

This neon green is not paint, and it fluoresces bright green

Photo by Lori Carter

A little history on the slag piles too

Click below for field trip policies

Copyright © Georgia Mineral Society, Inc.